Buying Bootstraps: How an Innovative Funding and Evaluation Model is Helping Get People Back on Their Feet

If you’re caught face-to-face with a large predator in the wild and escape isn’t an

option, become bigger. Wildlife experts advise you to stand at your full height,

exude authority, and appear as large (i.e., threatening) as possible.

If you’re caught face-to-face with a large predator in the wild and escape isn’t an

option, become bigger. Wildlife experts advise you to stand at your full height,

exude authority, and appear as large (i.e., threatening) as possible.

But what works with a mountain lion isn’t what works for humans.

“There’s a prevalent idea that the bigger and scarier the consequences of crime become, the more government agencies punish, the more people will change,” explained Christian Sarver, associate director of the University of Utah’s Utah Criminal Justice Center (UCJC). “Though the idea has a lot of support culturally, the research consistently shows that doesn’t work.” She explained that is a big part of why UCJC’s work is so important. “It’s too easy for interventions to be more influenced by political opinion than what science shows is effective. If we want better outcomes, programs need to be rooted in evidence-based practice.”

What does that actually look like? The most basic answer is that it can look a lot of different ways, which was part of the logic behind Salt Lake County’s innovative and recently completed Pay for Success program. This unique, $6.3 million six-year project changed not only the typical funding mechanisms for social service agencies; it also required agencies to consider novel, evidence-based solutions to better serve clients.

Funding for provision of social services often comes from government grants. Organizations apply for funding based on very specific requirements and are awarded money (or not), based in part on compliance to a very specific set of implementation guidelines. With Pay for Success, the funding structure was considerably different.

Organizations still applied to a government agency to receive funding, in this case Salt Lake County. But rather than the typical funnel of tax revenue --> Salt Lake County --> community social service providers, the funding for selected programs originated from privately owned banking institutions—a first for large scale social services funding. If the programs were shown to be successful, based on scientific evaluation, banks would receive a payment back from the County, plus interest—another incentive to choose programming that was based on scientific evaluation rather than political opinion. With this model, private banks and government agencies became partners in addressing social issues—banks providing the funding, with a separate entity overseeing programs to ensure both agencies and evaluators were in compliance with rigorous research guidelines.

Additionally, with Pay for Success, organizations were required to use the funding to support an innovative, randomized control trial, a highly rigorous, but uncommon research method within community-based, social service research. This was added in part to increase the scientific nature of the interventions and analyses used, and in part to increase reliance on evidence-based practice in program design and implementation.

What does “persistently homeless” mean?

In order to understand the efficacy of research, it’s important to have a clear understanding of who an intervention is designed to serve. In the case of the Homes Not Jail program, the intervention was designed for persistently homeless clients. The persistently homeless are defined as those individuals who have spent between 90 and 364 days over the previous year in emergency shelters, on the streets, or otherwise tracked as being homeless. These individuals spend long periods of time in emergency shelter and are commonly booked into jail for low-level crimes related to homelessness (e.g., public intoxication, trespassing). Ms. Cox explained, “This population was chosen in the hope that we could help people before they became chronically or permanently homeless."

Locally, two organizations were selected for grants through Salt Lake County’s program. First, The Road Home developed a rapid rehousing project, designed to help people who were persistently homeless. Usually, when housing programs are able to offer funding to clients, the support comes with some with very strict parameters: funding can only go toward specific housing costs, clients are required to pay 30% of their own income toward rent, are limited in how long they can receive assistance, etc. However, with Pay for Success, the Housing Not Jail program was able to offer flexible, needs-based support to help clients with whatever specific barriers they had to maintaining housing and employment while in the program—whether that was money to pay rent, buying a pair of work boots needed for the first day on a job, or helping a client requalify for an expired professional license.

Melissa Cox, division director of support housing at The Road Home, explained that this grant’s unusual level of adaptability was invaluable in helping clients. “The flexibility here was amazing. There is no quick solution to homelessness. Helping people takes time. But being able to help people with their personal, specific barriers went a long way to getting people the resources they needed.”

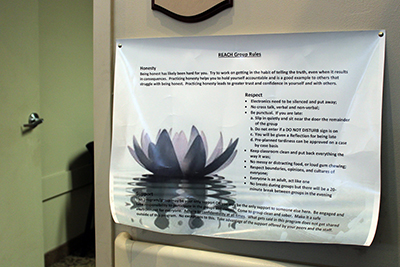

The second project was through First Step House, a Salt Lake County behavioral health service provider. First Step House has long used a variety of evidence-based methods and modalities to help clients overcome substance use disorders (SUDs), but they wanted to better address criminogenic need for clients who were involved in the criminal justice system and were at high risk of recidivism. They decided to use the Pay for Success grant funding to implement an assessment tool that could address these co-occurring needs.

Based on previous research, they created REACH—Recovery, Engagement, Assessment, Career,

Housing. REACH is an assessment-driven program that utilizes the Risk-Needs Responsivity

Model to identify and target therapeutic interventions that address all eight criminogenic

factors that contribute to criminal justice recidivism, including, but not limited

to, substance use disorders. It’s a broader, more wholistic approach meant to address

all the different facets of substance use. And so far, it has been very impactful.

First Step House Executive Director Shawn McMillen explained, “By expanding treatment

to address all risk factors that contribute to recidivism, we're seeing improvements

and treatment gains across the continuum. Further, and importantly, these treatment

gains seem to be durable—people are able to sustain those treatment gains over time.”

He continued, “At the agency level, in this space, we hardly ever get the opportunity

to know if what we did worked over time. On this project, REACH has demonstrated

that well designed, evidence-based services have impact.”

Based on previous research, they created REACH—Recovery, Engagement, Assessment, Career,

Housing. REACH is an assessment-driven program that utilizes the Risk-Needs Responsivity

Model to identify and target therapeutic interventions that address all eight criminogenic

factors that contribute to criminal justice recidivism, including, but not limited

to, substance use disorders. It’s a broader, more wholistic approach meant to address

all the different facets of substance use. And so far, it has been very impactful.

First Step House Executive Director Shawn McMillen explained, “By expanding treatment

to address all risk factors that contribute to recidivism, we're seeing improvements

and treatment gains across the continuum. Further, and importantly, these treatment

gains seem to be durable—people are able to sustain those treatment gains over time.”

He continued, “At the agency level, in this space, we hardly ever get the opportunity

to know if what we did worked over time. On this project, REACH has demonstrated

that well designed, evidence-based services have impact.”

Throughout Pay for Success’ six-year duration, the Utah Criminal Justice Center was involved in multiple aspects of these two projects, including research design, technical support, program evaluation, and outcome analysis. “One thing I love about my job is the broad range of work I’m able to do,” said UCJC Research Associate Professor Kort Prince. “We work in a very broad range of fields and use a variety of statistical analyses. As experts in research design and analysis, we’re able to bring methodological expertise that helps agencies do their work better.”

Mr. McMillen found UCJC’s expertise useful in very concrete ways. “They were able to help us evolve our thinking to what our model of care could and should look like to best serve our clients. The process was grueling, but it has helped us build our capacity in major ways.”

“Working with UCJC helped us think about data differently,” echoed Ms. Cox. “When we started collecting additional data, we were able to better identify who we were serving and pivot our services accordingly.” Pivot.

Over the last six years, these programs faced a global pandemic, significant policy changes, massive workforce changes, and skyrocketing housing prices. No research project, no matter how well designed, is equipped to seamlessly adjust to outside factors this substantial. However, despite the changes, multiple study outcomes showed both of these treatment programs were helpful, compared to treatment as usual, for the individual clients involved.

Helping agencies understand and articulate the data is core to what UCJC does, Dr. Sarver explained. “We don’t always have the subject matter expertise for specific issues, but we are able to help agencies understand how to show the real-world effect of the work they do.” Both The Road Home and First Step House found this to be true, both for this project and in the long term.

“Understanding the numbers really helped in telling the story to investors,” said Ms. Cox. “I was able to explain what was happening on the ground and explain why changes were needed, when they were. Now that we track this data, I can write grants more effectively because I can see the need more clearly.”

Mr. McMillen noted a similar impact. “Because of our work with UCJC, we were able to demonstrate our depth of knowledge about what would work, in addition to our passion, to our social impact investors. Our investor later told us that was what made them commit to our project.” He continued, “This project helped us develop the skills we needed to grow the organization and better serve our community.”